By Taylor Plimpton

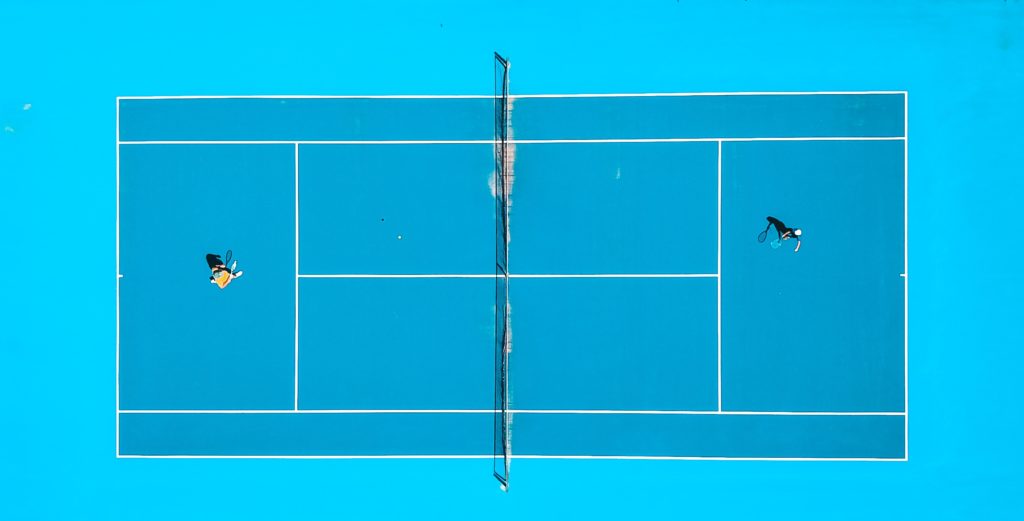

Every now and then, if you play enough tennis, a kind of mystical flow can be found—a Zen-like zone where you can seemingly do no wrong. You swing away freely, every shot you hit is crisp, your feet float across the court. Best of all, your self-critical, loudmouth ego has finally quieted. You feel a happy fatigue in your limbs, the sunshine on your skin; there is the pop of the tennis ball against your racket, the smell of summer in the air. You are, for once, wholly present.

Unfortunately, you are not Roger Federer or Rafael Nadal, the two players considered by many to be the greatest of all time, and this near-enlightened state of transcendent play rarely lasts long. Indeed, the next thing you know, you’ve smashed an overhead into the bottom of the net, and your silenced ego comes screaming back with a vengeance. Two miserable games later, that one little unforced error is still eating you up, and you cannot let it go.

Of course, in tennis, and in life, you have to learn to do exactly that: let go. “One thing that makes Rafa so great is that he has no short-term memory on the court.” This is how player, coach, commentator and Hampton native Paul Annacone puts the matter. “The great players don’t allow what has just happened to affect what is going to happen next.”

In other words, when they screw up—which even the best players do, multiple times, every match—they forget about it and move on. (You have to put the good points behind you as much as the bad ones, lest you find yourself patting yourself on the back and fantasizing about your inevitable victory: a sure way to lose not just the flow, but the match.) To remain truly present, the mind can’t stick to anything—the past, the future, success, failure—it has to be free of all that. You have to start each new point truly unencumbered.

Which is, of course how it is in life, too: Over and over, you have to find a way to begin again, to release the expanding burden of the past, shake yourself free from it, and start over fresh, as if the moment in front of you is the only one there ever was.

Me, I’ve always been a Federer fan—the effortless Zen in the way he plays, the grace he exhibits, the artistry, the ease—but when it comes to committing to the moment at hand, there has never been anyone like Nadal. It doesn’t matter what the score is: he never takes a point off. Every instant is as if it’s his first, his last, the only chance he’ll ever get. You can see the determination in his furrowed brow, hear it in every grunt, every “Vamos!” If Federer inhabits the zone naturally, Nadal unearths it with great intensity and focus: he wills himself there.

But how are we, mere mortals, supposed to find the flow—and if we lose it, how do we get it back? How do we re-inhabit the moment, when we are still cursing ourselves for that double-fault that lost us the first set, or daydreaming about what we might have for dinner?

We can emulate Nadal, and remember that it’s OK to forget, to pour ourselves completely into the moment. Thankfully, the physicality of sport in general can help us with this—the way it gets us out of our heads and into our bodies. Tennis, more specifically has developed various methods—often ridiculous-looking—for keeping its players focused and present: fiddling with your strings, bouncing the ball before you serve, hopping up and down. You don’t have to be as OCD as Nadal and towel off after every single point, but a ritual or two to center yourself, sure.

When I find myself sunk in the gloom of bad play, I try to remember that the point of all this is to have fun. You’re out here on a beautiful summer’s day, playing a game you love: every moment should be savored.

As Nadal reminds us, this moment, this point, is the only one you ever really get. What are you going to do with it?